Electromagnetism

high voltages and currents.

Electromagnetism encompasses various real-world electromagnetic phenomena. For example,

-

- See also: Optics

Magnetic lines of force of a bar magnet shown by iron filings on paper

Electromagnetism describes the interaction of charged particles with electric and magnetic fields. It can be divided into electrostatics, the study of interactions between charges at rest, and electrodynamics, the study of interactions between moving charges and radiation. The classical theory of electromagnetism is based on the Lorentz force law and Maxwell's equations.

Electrostatics is the study of phenomena associated with charged bodies at rest. As described by Coulomb’s law, such bodies exert forces on each other. Their behavior can be analyzed in terms of the concept of an electric field surrounding any charged body, such that another charged body placed within the field is subject to a force proportional to the magnitude of its own charge and the magnitude of the field at its location. Whether the force is attractive or repulsive depends on the polarity of the charge. Electrostatics has many applications, ranging from the analysis of phenomena such as thunderstorms to the study of the behavior of electron tubes.

Electrodynamics is the study of phenomena associated with charged bodies in motion and varying electric and magnetic fields. Since a moving charge produces a magnetic field, electrodynamics is concerned with effects such as magnetism, electromagnetic radiation, and electromagnetic induction, including such practical applications as the electric generator and the electric motor. This area of electrodynamics, known as classical electrodynamics, was first systematically explained by James Clerk Maxwell, and Maxwell’s equations describe the phenomena of this area with great generality. A more recent development is quantum electrodynamics, which incorporates the laws of quantum theory in order to explain the interaction of electromagnetic radiation with matter. Dirac, Heisenberg, and Pauli were pioneers in the formulation of quantum electrodynamics. Relativistic electrodynamics accounts for relativistic corrections to the motions of charged particles when their speeds approach the speed of light. It applies to phenomena involved with particle accelerators and electron tubes carrying

light is an oscillating electromagnetic field that is radiated from accelerating charged particles. Aside from gravity, most of the forces in everyday experience are ultimately a result of electromagnetism.

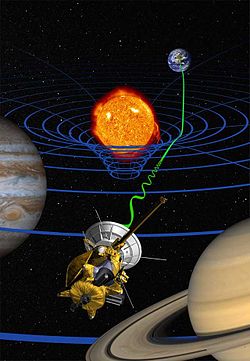

The principles of electromagnetism find applications in various allied disciplines such as microwaves, antennas, electric machines, satellite communications, bioelectromagnetics, plasmas, nuclear research, fiber optics, electromagnetic interference and compatibility, electromechanical energy conversion, radar meteorology, and remote sensing. Electromagnetic devices include transformers, electric relays, radio/TV, telephones, electric motors, transmission lines, waveguides, optical fibers, and lasers.